Abstract: This article describes the various aspects of the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) and its suitability as a library classification system for classifying library resources. It begins with an introduction, recounting its history and development, leading up to an explanation of principles, structure, tables, and notation. This is followed by number building examples with MARC 21 coding for LCC numbers. LCC tools and aids are listed thereafter with a description of the use of technology for efficient and consistent number building, and the process of proposing new numbers online to be added to the LCC schedules. Finally, analyzing both its advantages and criticisms it concludes that LCC is a suitable classification system for libraries.

Keywords: Library of Congress Classification; LCC; LC Classification

Contents

- Library of Congress Classification - Introduction

- History and Development

- LCC Principles and Structure

- Main Classes

- Subclasses

- Divisions

- Schedule Format

- Preface

- Contents Page

- Outline

- The Body of the Schedule

- Tables

- Index

- Notation

- Symbols

- Expressiveness

- Hospitality

- Mnemonics

- Brevity

- Building a Call Number

- Marc 21 Coding for Call Numbers

- Indicators

- Subfield Codes

- Tools and Aids for LC Classification

- LCC Print Schedules

- SuperLCCS

- Classification Web

- Classification and Shelflisting Manual (CSM)

- LCC Outline

- Cataloging Calculator

- Library of Congress (LCC) Approved Lists

- Name Authority Records

- Proposing a New Class Number in LCC

- Evaluation of the Library of Congress Classification

- Advantages of LCC

- Criticisms of LCC (and Criticism of Criticisms)

- Conclusion

- Library of Congress Classification Articles and News

- Library of Congress Classification Quiz

- Library of Congress Classification Videos

- Library of Congress Classification Training for Advanced Learners

- References

List of Figures

Following is the list of figures used in this article. Please note that if you click on some image then it will appear in full enlarged view.

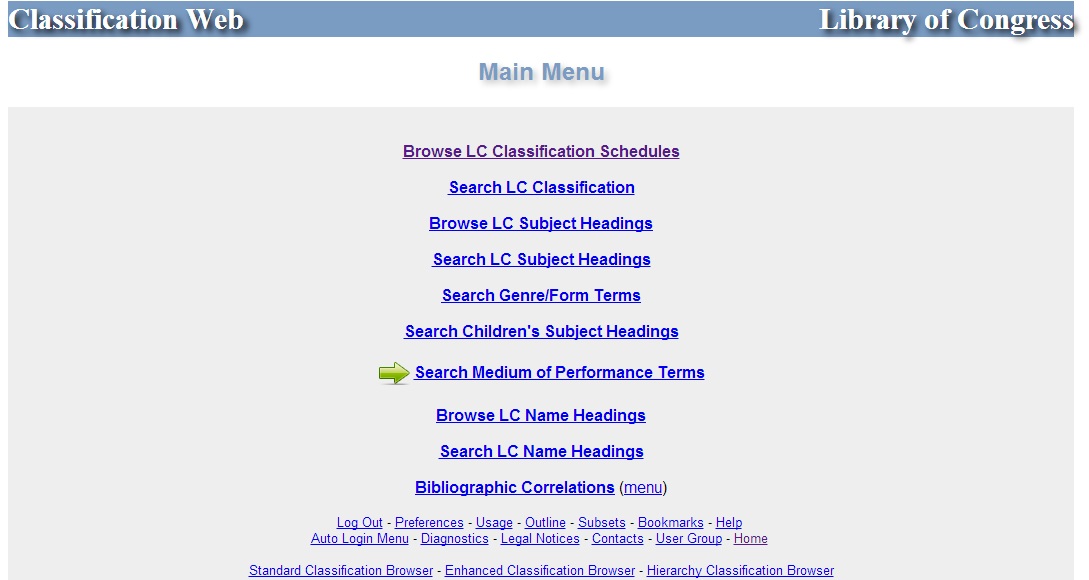

1 Main Menu of Classification Web

2 Example of Classification Web display

3 Classification and Shelflisting Manual in Cataloger’s Desktop

4 Library of Congress Approved List

5 Literary Author Number in LC Name Authority Record

6 LCC Classification Proposal Menu – Classification Web

7 LCC Classification Proposal Example

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION - INTRODUCTION

The Library of Congress Classification (LCC) is a system of library classification developed by the Library of Congress. It was developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to organize and arrange the book collections of the Library of Congress. Over the course of the twentieth century, the system was adopted for use by other libraries as well, especially large academic libraries in the United States. It is currently one of the most widely used library classification systems in the world. The Library's Policy and Standards Division maintains and develops the system¹. In recent decades, as the Library of Congress made its records available electronically through its online catalog, more libraries have adopted LCC for both subject cataloging as well as shelflisting.

There are several classification schemes in use worldwide. Besides LCC, the other popular ones among them are Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), Universal Decimal Classification (UDC), and Bliss Bibliographic Classification (BC). Out of these, DDC and LCC are the classification systems which are most commonly used in libraries.

The potential of Library of Congress Classification (LCC) system is yet to be explored in libraries. This article describes the various aspects of LCC and its suitability as a library classification system for classifying library resources.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

Main article: Library of Congress Classification (LCC) History and Development

The Library of Congress was established in 1800 when the American legislatures were preparing to move from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington, D.C. Its earliest classification system was by size and, within each size group, by accession number. First recorded change in the arrangement of the collection appeared in the library’s third catalog, issued in 1808, which showed added categories for special bibliographic forms such as legal documents and executive papers².

On the night of August 24, 1814, during the war of 1812, British soldiers set fire to the Capitol, and most of the Library of Congress’s collections were destroyed. Sometimes after, Thomas Jefferson offered to sell to Congress his personal library; subsequently, in 1815, the Congress purchased Jefferson’s personal library of 6,487 books. The books arrived already classified by Jefferson’s own system. The library adopted this system and used it with some modifications until the end of the nineteenth-century ³.

Library of Congress moved to a new building in 1897. By this time, the Library’s collection had grown to one and a half million volumes and it was decided that Jefferson’s classification system was no longer adequate for the collection. A more detailed classification scheme was required for such a huge and rapidly growing collection of documents. The Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), Cutter’s Expansive Classification and the German Halle Schema were studied, but none was considered suitable. It was decided to construct a new system to be called the Library of Congress Classification (LCC). James C.M. Hanson, Head of the Catalog Division, and Charles Martel, Chief Classifier, were made responsible for developing the new scheme. Hanson and Martel concluded that the new classification should be based on Cutter’s Expansive Classification⁴ as a guide for the order of classes, but with a considerably modified notation. Work on the new classification began in 1901. The first outline of the Library of Congress Classification was published in 1904 by Charles Martel and J.C.M. Hanson – the two fathers of Library of Congress Classification. Class Z (Bibliography and Library Science) was chosen to be the first schedule to be developed. The next schedules, E-F (American history and geography), were developed. But E-F were the first schedules to be published, in 1901, followed by Z in 1902. Other schedules were progressively developed. Each schedule of LCC contains an entire class, a subclass, or a group of subclasses. The separate schedules were published in print volumes, as they were completed. All schedules were published by 1948, except the Class K (Law). The first Law schedule—the Law of United States, was published in 1969, and the last of the Law schedules to publish was KB—Religious law, which appeared in 2004.

From the beginning, individual schedules of LCC have been developed and maintained by subject experts. Such experts continue to be responsible for additions and changes in LCC. The separate development of individual schedules meant that, unlike other classification systems, LCC was not the product of one mastermind; indeed, LCC has been called “a coordinated series of special classes”⁵.

Until the early 1990s, LCC schedules existed mainly as a print product. The conversion of LCC to machine-readable form began in 1993 and was completed in 1996. The conversion to electronic form was done using USMARC (now called MARC21) Classification Format. This was a very important development for LCC, as it enabled LCC to be consulted online and much more efficient production of the print schedules.

In the year 2013, the Library of Congress announced a transition to online-only publication of its cataloging documentation, including the Library of Congress Classification. It was decided, the Library’s Cataloging Distribution Service (CDS) will no longer print new editions of its subject headings, classification schedules, and other cataloging publications. The Library decided to provide free downloadable PDF versions of LCC schedules. For users desiring enhanced functionality, the Library’s two web-based subscription services, Cataloger’s Desktop and Classification Web will continue as products from CDS. Classification Web is a web-based tool for LCC and LCSH. It supports searching and browsing of the LCC schedules and provides links to the respective tables to build the class numbers for library resources. LC has also developed training materials on the principles and practices of LCC and made those available for free on its website.

Main article: Library of Congress Classification (LCC) History and Development

On the night of August 24, 1814, during the war of 1812, British soldiers set fire to the Capitol, and most of the Library of Congress’s collections were destroyed. Sometimes after, Thomas Jefferson offered to sell to Congress his personal library; subsequently, in 1815, the Congress purchased Jefferson’s personal library of 6,487 books. The books arrived already classified by Jefferson’s own system. The library adopted this system and used it with some modifications until the end of the nineteenth-century ³.

Library of Congress moved to a new building in 1897. By this time, the Library’s collection had grown to one and a half million volumes and it was decided that Jefferson’s classification system was no longer adequate for the collection. A more detailed classification scheme was required for such a huge and rapidly growing collection of documents. The Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC), Cutter’s Expansive Classification and the German Halle Schema were studied, but none was considered suitable. It was decided to construct a new system to be called the Library of Congress Classification (LCC). James C.M. Hanson, Head of the Catalog Division, and Charles Martel, Chief Classifier, were made responsible for developing the new scheme. Hanson and Martel concluded that the new classification should be based on Cutter’s Expansive Classification⁴ as a guide for the order of classes, but with a considerably modified notation. Work on the new classification began in 1901. The first outline of the Library of Congress Classification was published in 1904 by Charles Martel and J.C.M. Hanson – the two fathers of Library of Congress Classification. Class Z (Bibliography and Library Science) was chosen to be the first schedule to be developed. The next schedules, E-F (American history and geography), were developed. But E-F were the first schedules to be published, in 1901, followed by Z in 1902. Other schedules were progressively developed. Each schedule of LCC contains an entire class, a subclass, or a group of subclasses. The separate schedules were published in print volumes, as they were completed. All schedules were published by 1948, except the Class K (Law). The first Law schedule—the Law of United States, was published in 1969, and the last of the Law schedules to publish was KB—Religious law, which appeared in 2004.

From the beginning, individual schedules of LCC have been developed and maintained by subject experts. Such experts continue to be responsible for additions and changes in LCC. The separate development of individual schedules meant that, unlike other classification systems, LCC was not the product of one mastermind; indeed, LCC has been called “a coordinated series of special classes”⁵.

Until the early 1990s, LCC schedules existed mainly as a print product. The conversion of LCC to machine-readable form began in 1993 and was completed in 1996. The conversion to electronic form was done using USMARC (now called MARC21) Classification Format. This was a very important development for LCC, as it enabled LCC to be consulted online and much more efficient production of the print schedules.

In the year 2013, the Library of Congress announced a transition to online-only publication of its cataloging documentation, including the Library of Congress Classification. It was decided, the Library’s Cataloging Distribution Service (CDS) will no longer print new editions of its subject headings, classification schedules, and other cataloging publications. The Library decided to provide free downloadable PDF versions of LCC schedules. For users desiring enhanced functionality, the Library’s two web-based subscription services, Cataloger’s Desktop and Classification Web will continue as products from CDS. Classification Web is a web-based tool for LCC and LCSH. It supports searching and browsing of the LCC schedules and provides links to the respective tables to build the class numbers for library resources. LC has also developed training materials on the principles and practices of LCC and made those available for free on its website.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION PRINCIPLES AND STRUCTURE

Library of Congress Classification is an enumerative system of library classification which classifies by discipline, i.e. a system that lists numbers for single, compound, as well as complex subjects.

Main classes of LCC represent major disciplines which are divided into subclasses which are further divided into divisions. Such a categorization creates a hierarchical display for LCC, progressing from the general to the specific. Levels of hierarchy in the schedules are indicated by indentions.

The schedules of LCC were developed independently by the different group of subject specialists based on the “literary warrant” of the materials already in, and being added to, the Library of Congress. Therefore, each schedule stands on its own with some differences from discipline to discipline; because of their intrinsic peculiarities.

Main Classes

LCC divides the entire field of knowledge into 21 main classes, each identified by a single capital letter of the alphabet⁶. The letters I, O, W, X, Y have not been assigned subject areas but could be used for future expansion.

Subclasses

Each of the main classes, with the exception of E and F, is further divided into subclasses, which represent disciplines or major branches of the main class. Most subclasses are denoted by two letter, or occasionally three-letter combinations. For example, following are some subclasses of class P.

Divisions

Each subclass is further subdivided into divisions that represent components of the subclass to specify form, place, time & subtopics. These are denoted by integers 1-9999, some with decimal extension. Some subtopics may also be denoted by a Cutter number (e.g., .S35).

For example, following are some divisions of subclass PK.

Subclass PK

PK1-(9601) Indo-Iranian philology and literature

PK1-85 General

PK101-2899 Indo-Aryan languages

PK101-185 General

PK(201)-379 Vedic

PK401-976 Sanskrit

PK1001-1095 Pali

PK1201-1409.5 Prakrit

PK1421-1429.5 Apabhramsa

PK1471-1490 Middle Indo-Aryan dialects

PK1501-2899 Modern Indo-Aryan languages

PK1550-2899 Particular languages and dialects

PK1550-1569 Assamese

PK1651-(1799) Bengali

PK1801-1831.95 Bihari

PK1841-1870.95 Gujarati

PK1931-2212 Hindi, Urdu, Hindustani languages and literatures

PK1931-1970 Hindi language

PK1971-1979.5 Urdu language

PK1981-2000 Hindustani language

PK2030-2142 Hindi, Hindustani literatures

PK2151-2212 Urdu literature

Schedule Format

There are 41 printed volumes of individual classification schedules for the main classes and subclasses of LCC. Each print schedule consists of a preface, a contents page, broad outline of the schedule, followed by the main body of the schedule, tables, and index.

Preface

The preface gives the history of the schedule and the changes from previous editions.

Contents Page

The contents page lists the outline, subclasses, tables, and index for the schedule.

Outline

The outline consists of a detailed summary of the topics as well as subtopics. First, there is a broad outline with subclasses, which serves as the table of contents in the print schedules. It is followed by a detailed outline with 2 or 3 levels of hierarchy.

The Body of the Schedule

Different group of subject specialists were responsible for the development of individual classes, therefore a given class may display unique features. The use of tables and the degree and method of notational synthesis often vary from schedule to schedule. However, certain features are shared by all schedules: the overall organization, the notation, the method and arrangement of form and geographic divisions, and many tables. The organization of divisions within a class, subclass, or subject originally followed a general pattern, often called Martel’s seven points. Briefly, these are. (1) general form divisions: periodicals, societies, collections, dictionaries or encyclopaedias, conference, exhibition or museum publications, directories, yearbooks, etc.; (2) theory, philosophy; (3) history, biography; (4) treatises or general works; (5) law, regulation, state relations; (6) study and teaching, research; and (7) special subjects and subdivisions of subjects. Subsequent additions and changes have clouded this pattern to some extent, but it is generally still discernible. Since the development of K (Law) schedules, legal topics relating to specific subjects have been moved to class K (Chan 2007). This pattern of arrangement is a progression from the general to the specific.

Indentation of captions is used throughout the schedules and is important in showing the hierarchical relationships to topics and subtopics. Notes may accompany LC class numbers and headings. They can indicate the scope of that number or may refer the classifier to another number or section of the schedule⁷.

Tables

Tables are used extensively in LCC to allow to assign a more specific number and to allow for sub-arrangement of similar topics without the need to print the same instruction repeatedly, thereby saving space.

Tables in LCC can be categorized into three types: Internal tables, External tables, and Tables of general application.

Internal tables appear within the text of the schedule that applies to a specific subject or span of numbers. External tables appear at the end of the schedule, before the index, that applies to various subjects in a class or subclass. Tables of general application appear in Classification and Shelflisting Manual⁸ which are applicable throughout the schedules. Tables of general application include the biography table, the translation table, and the geographic tables based on Cutter numbers.

Index

There is a detailed index accompanying each schedule in the back of the print version. Index entries refer to a specific LCC number in that schedule. It is important to note that there is no index to the LCC schedules for the print version. A combined index for the entire scheme exists only in the online version accessible and browsable through the Classification Web⁹.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION NOTATION

The notation of a classification scheme is the series of symbols that stand for the classes, subclasses, divisions, and subdivisions of classes.

Symbols

LCC uses a mixed alphanumeric notation of the Roman capital letters, Arabic numerals, and a dot (.) to construct call numbers. A single letter denotes a main class and most subclasses are designated by double letters. Triple-letter combinations have been used only for some subclasses in D and K schedules. Divisions within subclasses are denoted by Arabic numbers; they are used integrally, from 1 to 9999 if necessary, with gaps left liberally to accommodate new topics as they arise¹º. A decimal extension is used when it is necessary to insert a topic between two consecutive whole numbers. Further subdivision is indicated by adding Cutter numbers (a combination of a capital letter and one or more numerals). This completes the class number part of the call number. The call number is completed by adding an item number or book number to the class number which is based on the main entry (primary access point, the author or title) in the form of an alphanumeric Cutter number, plus, in most cases the year of publication.

Expressiveness

Expressiveness has to do with the capacity of the notational system to “express” the hierarchical and coordinate relationships of the subjects which the notation represents. The LCC notation has limited expressiveness in comparison to other universal book classification schemes and, especially in comparison to the DDC¹¹. LCC notation is not hierarchical beyond the class-subclass level, i.e. LCC notation does not reflect all the general-specific relationships that are inherent in the classification scheme.

Hospitality

Hospitality has to do with a notation’s capacity to accommodate new concepts or subjects as necessary in the schedules. It should allow for the insertion of both subordinate and coordinate subjects¹². In this sense, the hospitality of the LCC notation is enormous, provisions for new subject matter can be easily added to the system.

At the level of main class letters I, O, X, and Y have not been assigned to any subjects and are available for later use. At the level of the subclass, gaps have been left between two-letter combinations, which can be used for future expansion. Also, there is an option of interpolating three-letter combinations to denote new subclasses. Subclasses can be further expanded by the use of decimal extension and Cutter numbers.

Mnemonics

These are memory-aiding devices used in the notation of classification schemes that enable an enquirer to associate a certain symbol arrangement with a certain subject concept. They may occur by the use initial letters to indicate certain classes.

LCC notation lacks mnemonic aids. Some use of mnemonics can be seen in Class A, where the second letter of the subclass is taken from the name of the subject covered. For example, AC for Collections, AE for Encyclopaedias, AN for Newspapers, AS for Societies, etc.

Brevity

Brevity refers to the length of the notation to express the same concept. Notation should be as brief as possible. LCC notation results in relatively brief class numbers when compared to other classification schemes like DDC. It allows more combinations and greater specificity without long notations.

BUILDING A CALL NUMBER USING LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION

Following are some examples of building LCC call numbers:

1. A history of Hindi literature by K.B. Jindal, published in 1993.

2. Statistics for management, by Richard I. Levin and David S. Rubin, published in 1998.

3. An autobiography: the story of my experiments with truth, by Mahatma Gandhi, 2004. Autobiography of Mahatma Gandhi translated into English.

4. Fostering e-governance: compendium of selected Indian initiatives, edited by Piyush Gupta, R.K. Bagga, and SrideviAyaluri, published in 2009.

5. Walking with the Buddha: Buddhist pilgrimages in India, edited by Swati Mitra, published in 1999.

MARC 21 CODING FOR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION CALL NUMBERS

In MARC 21 Format for Bibliographic Data (Library of Congress. 2014d), the LC call number appears in 050 field.

050 00 $a PK2031 $b .J56 1993

050 14 $a JQ229.A8 $b F67 2009

Indicators

First indicator - Existence in LC Collection

# (blank) - No information provided (used when a call number assigned by an organization other than LC)

0 - Item is in LC

1 - Item is not in LC

Second indicator - Source of Call Number

0 - Assigned by LC

4 - Assigned by agency other than LC

Subfield Codes

$a - Classification number

$b - Item number

Subfield $a may be repeated to record an alternative class number.

Other subfields are defined in the MARC 21 format, viz., $3, $6, and $8, but are not commonly used in general cataloging.

Additionally, 090 field can be used in MARC coding in OCLC for locally assigned LC-type call number where both indicators are blank.

TOOLS AND AIDS FOR LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION

LCC is available in print and electronic format. There are some other tools and aids which describe and help in the application of LCC in practice.

LCC Print Schedules

The print edition is available in 41 separate volumes which can be purchased individually or as a set from the Cataloging Distribution Service of Library of Congress. Revision and expansion of LCC take place continuously. New revised edition of a particular schedule is published when there are sufficient changes.

SuperLCCS

Thompson Gale issues annually a print version of LCC schedules known as SuperLCCS, which combine each classification schedule with all the additions, changes, and deletions through the previous year. SuperLCCS is also available on microfiche¹³.

Classification Web

The electronic version of LCC is available online as Classification Web (http://classificationweb.net/). Fig. 1 shows the main menu and Fig. 2 shows the display of LCC numbers of Classification Web. It includes a full-text display of the entire LCC, LCSH, plus correlations between LCC and LCSH. Classification Web is most up-to-date version. It is updated daily and heavily used.

Fig. 1 Main Menu of Classification Web

Fig. 2 Example of Classification Web display

Classification and Shelflisting Manual (CSM)

The purpose of this publication is to provide guidelines for establishing Library of Congress classification numbers and assigning them to library materials, as well as for shelflisting materials collected by the Library of Congress. It is an accumulation of guidelines that have been formulated over several decades dealing with commonly recurring questions that arise when using the LC classification. Fig. 3 shows the display of Classification and Shelflisting Manual in Cataloger’s Desktop, an online product available for subscription from the Library of Congress.

Fig. 3 Classification and Shelflisting Manual in Cataloger’s Desktop

An outline of the LCC is available online on LC website at www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/lcco/ containing files in PDF and WordPerfect format for all the main classes of LCC with the caption of the subclasses and some more information.

Cataloging Calculator

This is an online tool, available at http://calculate.alptown.com/ can be used for deriving Cutter Numbers

Library of Congress (LCC) Approved Lists

Additions and changes to LCC which are proposed by catalogers and approved by the editorial committee of LCC are communicated to the library professionals through LCC Weekly Lists¹⁴ (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Library of Congress Approved List

Weekly lists are also available now as RSS feeds.

Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)

LCSH¹⁵ is available in print and online through Classification Web and Library of Congress Website. Many LCSH entries refer in a bracket to one or more class numbers, often including terms for captions used in the schedules, though such class number is not always kept up-to-date.

Classification Web has a very useful feature, viz. LCSH to LCC correlations. While subject cataloging usually subject headings are provided first using LCSH, where the first entry is based on the predominant topic. Then this LCSH to LCC correlation feature is used to ascertain the appropriate LC class number.

Name Authority Records

Literary Author Number (LAN) is assigned to literary authors which is recorded in the MARC field 053 of the name authority record (NAR). Following is an example (Fig. 5) of a Library of Congress Name Authority Record showing a LAN to William Shakespeare.

PROPOSING A NEW CLASS NUMBER IN LCC

In 2006, an automated Minaret-based classification proposal system replaced the former manual worksheet-based system (Fig. 6). It can be accessed online at the URL: http://classificationweb.net/Menu/proposal.html

Fig. 6 LCC Classification Proposal Menu – Classification Web

This automated system is used to propose a new classification number, to propose a new reference, or to modify an existing number. Following is an example (Fig. 7) of a recently made classification proposal for an Indian caste “Telis”, which was later approved and included in the LCC schedules.

Fig. 7 LCC Classification Proposal Example

EVALUATION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION

LCC like any other classification system has both strengths as well as weak points. Many of the criticisms labeled against LCC are no longer valid now or becoming less true with the automation of the schedules and the introduction of Classification Web.

Advantages of LCC

1. LCC is highly enumerative by listing all subjects of the past, the present, and the anticipatable future. Because of this LCC class numbers required very less notational synthesis and therefore the scheme is very easy to use. This feature is very useful for classifying holdings of large libraries having a comprehensive collection on all subjects, as it facilitates unique class numbers for a wide range of subjects.

2. LCC schedules are developed, revised, and maintained by subject experts rather than by generalists.

3. LCC is the most continuously revised classification scheme. The Classification Web database is updated daily incorporating new additions and changes proposed by catalogers and approved by the editorial committee of LCC.

4. LCC provides cooperative opportunity to introduce new numbers. New class numbers are proposed by catalogers at LC, its five overseas offices¹⁶, and SACO¹⁷, member libraries, covering all the regions and languages of the world.

5. Classification Web, the World Wide Web interface of LCC has made number building in LCC very easy by its various advanced search features.

6. LCC notation results in relatively brief class numbers when compared to other classification schemes, like DDC.

7. LCC notation is enormously hospitable and expandable. New classes, subclasses, divisions, and topics can be conveniently added without requiring wholesale revision.

8. LCC allows each work to be uniquely classified with the help of techniques like the use of Cutter numbers, expansion of decimal numbers and adding of the date of publication.

9. Classification and Shelflisting Manual (CSM) provides comprehensive theory and guidelines on how to use LCC.

10. LCC numbers are available widely for copy cataloging purposes from Library of Congress online catalog¹⁸ and many records in OCLC’s WorldCat (Online Computer Library Center 2014).

11. Application of LCC numbers is found to be very consistent. A study on the consistency of LCC and their implications for union catalogs concluded that under the condition that a library system has a title, the probability of that title having the same LCC-based class number across library systems is greater than 85 percent¹⁹.

12. LCC has the support of the resources of Library of Congress which ensures its dependability and future for wider use.

Criticisms of LCC (and Criticism of Criticisms)

1. LCC schedules lack consistency. (Different schedules are developed and maintained by respective subject experts so they do lack consistency but this can also be seen as an advantage as it allowed each schedule to be developed according to its own unique structure).

2. LCC has no overall index. (True for the print format of schedules only, online version includes a unified index).

3. Scope notes of LCC are less descriptive. (Less required due to vast enumeration of subjects).

4. LCC is based on the literary warrant from the collections of Library of Congress and reflects national bias. (Becoming less true day by day: see point 4 under “Advantages of LCC”).

5. There are little documentation and guidelines for the subject analysis. (No longer valid with the publication of a unified Classification and Shelflisting Manual in Cataloger’s Desktop).

6. LCC is too large for a classifier to fully master and there is a time lag between the revised edition of the schedules (Classification Web overcomes these two criticisms as it is updated daily and its advanced search feature enable ease of use).

7. Multi-topical compound subjects are difficult to classify. (All the classification schemes face this problem. For a book which is classified for shelving purposes, a single unique call number has to be provided the base on the predominant topic of the book, but in case of electronic documents many call numbers can be given for every significant subject contained in the document for efficient retrieval).

8. Revision of the schedules sometimes requires reclassification decisions. For instance, the increasing number of books on Buddhism prompted its removal from the subclass BL to a new subclass BQ.

9. Some parts of LCC are obsolete and reflect 19th/early 20th-century worldview. (Sometimes required for maintaining the stability of the system and minimizing the need for reclassification).

10. Costly print schedules and subscription of the online version. (LC has made LCC schedules free as downloadable PDF files along with training documentation free on its website)

CONCLUSION

LCC is well established and has been used for many years by prominent libraries in the United States and other countries. During the last century, the role of LCC has been expanded from a tool for locating the holdings of a library on shelves to a tool for browsing them through the online catalog, and more recently for organizing and providing access to electronic and networked resources. The role of LCC as a knowledge organization system is yet to be exploited fully in the current environment. LCC has great potential as a means for organizing web resources. It can assist with browsing and with narrowing or broadening of searches. There has been an effort by LC to make available LCC as Linked Data.²⁰ LCC schedules can be used to build specialized classification schemes for effectively organizing web resources in digital libraries in specific subject areas. LCC and Classification Web together become a great combination as a tool for efficient organization, management, and retrieval of information. LCC with its well-defined categories, well-developed hierarchies, worldwide use, and mapping to other subject schemas like LCSH holds promise in a variety of applications beyond its familiar role as a shelf location device. The scheme appears to remain a classic example of an enumerative scheme which has proved successful over the years and has great future being the scheme used by the biggest and most influential library of the world, the Library of Congress.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION ARTICLES AND NEWS

List of articles and news on Library of Congress Classification from Library and Information Science Articles and News--Please refer to this article and locate articles and news items given below under the heading "CLASSIFICATION & SHELFLISTING" where you will also find their URLs.

List of articles and news on Library of Congress Classification from Library and Information Science Articles and News--Please refer to this article and locate articles and news items given below under the heading "CLASSIFICATION & SHELFLISTING" where you will also find their URLs.

- Library of Congress Discontinues NACO Literary Author Number Program (July 1, 2018) - All works by or about an individual literary author are generally classified together in the same number or span of numbers in class P, although multiple numbers or spans of numbers may be established for authors who write in more than one language. To allow for a high level of consistency, the classification number assigned to an author may be recorded in the author’s name authority record. In the past, the Library of Congress has accepted suggestions for literary author numbers from NACO members; those suggestions would be reviewed by LC staff and included in the name authority record as “LC‐verified.” The program by which NACO members could suggest literary author numbers to LC has been discontinued.

- Library of Congress Classification training materials in OCLC WebJunction Course Catalog - the presently available courses and webinars are listed here: (1) Library of Congress Classification (LCC): Intermediate (Webinar - Self-enrollmentment) - This session will focus on the selection and construction of LC Classification (LCC) call numbers for literature, maps and atlases, and moving images, including the construction of cutters for literary works and juvenile belle lettres. (2) Library of Congress Classification (LCC): Introduction (Webinar - Self enrollment) - This session will briefly introduce the history of LC Classification (LCC) and the general principles of classification. Participants will be introduced to the Classification and Shelflisting Manual and learn how to make use of Classification Web, Authorities.loc.gov and the freely-available LCC schedules to select classification numbers. There will be special focus on the use of the LC Cutter table and when to use it. (3) Shelving with Library of Congress Classification (Self-paced Course - Self enrollment) - This course provides a great introduction for any library staff, assistants or volunteer needing to learn how to shelve items by the classification system used by the Library of Congress (LC). One of the most time-consuming tasks for library staff is training assistants and volunteers about classification systems and how to properly shelve materials. Few tasks are more vital for shelf maintenance and patron access. This lesson provides online training that will help new staff members and volunteers become productive as quickly as possible with a minimum of time investment by the professional librarian. After completing this training, the learner will be able to accurately read shelves and properly file materials according to Library of Congress (LC) standards.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION QUIZ

- Who Developed Library of Congress Classification System? [(a) Charles Martel (b) Herbert Putnam (c) James C.M. Hanson (d) James C.M. Hanson and Charles Martel]

- Which was the first Library of Congress Classification (LCC) schedule to be published? [(a) Z (Bibliography and Library Science) (b) L (Education) (c) K (Law) (d) E-F (American history and geography)]

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION VIDEOS

Videos on Library of Congress Classification from the article Library and Information Science Videos. These videos are in the form of a playlist created in the YouTube channel of Librarianship Studies & Information Technology. Just click on the top-left side of the video to get the list of videos in the playlist from where you can choose the desired video to watch.

Videos on Library of Congress Classification from the article Library and Information Science Videos. These videos are in the form of a playlist created in the YouTube channel of Librarianship Studies & Information Technology. Just click on the top-left side of the video to get the list of videos in the playlist from where you can choose the desired video to watch.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION TRAINING FOR ADVANCED LEARNERS

REFERENCES

2. LaMontagne Leo E, American library classification with special reference to the Library of Congress (Shoe String Press; Hamden, CT), 1961, p. 44-45.

3. Chan Lois Mai, Library of Congress Classification in a new setting: beyond shelf marks. Available at http://2008.myvote.org/www.loc.gov/cds/chanarticle.html (Accessed on 23 April 2017)

4. Cutter C A, Expansive Classification. Part I: the first six classifications (C. A. Cutter; Boston, MA), 1893.

5. Maltby A, Sayers’ manual of classification for librarians, 5th edn (Andre Deutsch; London), 1975, p. 175.

6. Library of Congress, Library of Congress Classification outline. Available at http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/lcco/ (Accessed on 23 April 2017)

7. Dittmann H and Hardy J, Learn Library of Congress Classification, 2nd edn (Total Recall Publications Inc; Friendswood, Texas), 2007, p. 30.

8. Library of Congress, Classification and Shelflisting Manual. Available at http://desktop.loc.gov (Accessed on 23 April 2017)

10. Foskett A C, The subject approach to information, 5th edn (Library Association Publishing; London), 1996, p. 325.

11. Miksa F, The Library of Congress Classification. Available at https://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~l384k3fm/Franm/CatIEs-c09-p1-29-020306.pdf (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

12. Hunter E J, Classification made simple (Gower Publishing Company; Aldershot), 1988, p. 61.

13. Gale Research Inc., Super LCCS: Gale’s Library of Congress Classification schedules combined with additions and changes (Gale Research Inc.; Detroit), 1994.

14. Library of Congress, Library of Congress Classification (LCC) Approved Lists. Available at http://www.loc.gov/aba/cataloging/classification/weeklylists/ (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

15. Library of Congress, Library of Congress Subject Headings. Available at http://www.loc.gov/aba/publications/FreeLCSH/freelcsh.html (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

16. Library of Congress, Overseas Offices. Available at http://www.loc.gov/acq/ovop/ (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

17. Library of Congress, SACO – Subject Authority Cooperative Program. Available http://www.loc.gov/aba/pcc/saco/ (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

18. Library of Congress, Library of Congress Online Catalog. Available at http://catalog.loc.gov (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

19. Subrahmanyam B, Library of Congress classification numbers: issues of consistency and their implications for union catalogs, Library Resources & Technical Services, 50(2) (2006) 110-119.

20. Library of Congress, Linked Data Service, LC Classification. Available at http://id.loc.gov/authorities/classification (Accessed on 23 April 2017).

21. Library of Congress Classification: Online Training. Available at https://www.loc.gov/catworkshop/lcc/index.html (Accessed on17 June 2020).

USED FOR

- LCC

- LC Classification

SEE ALSO

NOTE

- This article was originally published in Annals of Library and Information Studies (ALIS) which is a leading quarterly journal (ranked number one in India) in Library and Information Studies publishing original papers, survey reports, reviews, short communications, and letters pertaining to library science, information science and computer applications in these fields. The founding editor of ALIS was Dr. S. R. Ranganathan. This article is revised and enlarged here and will gradually be developed to become the most informative place for Library of Congress Classification (LCC). Bookmark, visit frequently and share this article.

HISTORY

- Last Updated: 2020-06-17

- Written: 2017-11-23

FEEDBACK

- Help us improve this article! Contact us with your feedback. You can use the comments section below, or reach us on social media.

Some comments received on this article are given below:

- Prof. Wajih A. Alvi, X Professor, University of Kashmir, X Professor under UNDP in Ethiopia, X University Librarian, IUST, Kashmir [April 4, 2018, e-mail] -- Dear Salman Haider Saheb, Ya, of course, we have not met, but your slices of information on various facets of LIS do disclose your professional commitment and competencies every now and then. I appreciate a great deal. Your message regarding LCC too was quite comprehensive. However, you have included CC in popular schemes. I do not agree here. Count the libraries that use CC in India and you will not find the number even in double figure. It was a scheme with a thorough theoretical base, no doubt. But its epitaph was written on the death of SR Ranganathan. I have visited university libraries where this scheme was introduced decades back. People there toss their heads as they cannot now switch over to any other scheme. In India, professional schools used to retain the theory and practice of this scheme in their courses of studies. But now the trend is changing as we are prompted to accommodate ICT related topics to make the professional education relevant to the changing library landscape. The schemes like UDC, DDC, LCC, on the other hand, are alive and relevant as their people attend to them and spend on their updating and makeup. [Please note that based on this feedback of Prof. Alvi, we have removed CC from the mention of popular library classification schemes]